|

Interview Podcast Alec Soth

|

|

0:00:00

0:05:00

|

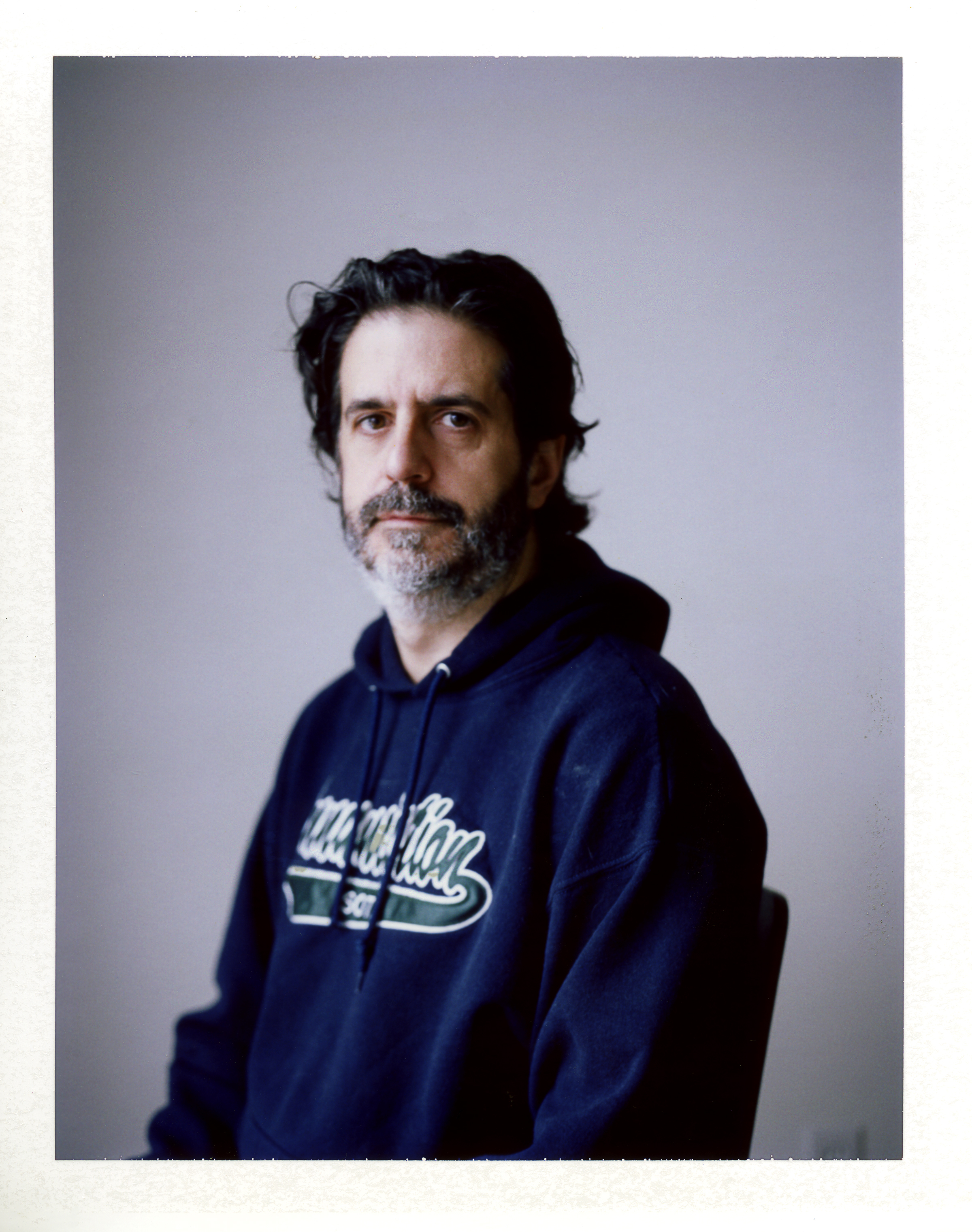

Alec Soth is an award-winning American photographer, artist, and independent publisher based in Minneapolis. Alec’s work occupies a fascinating, liminal territory between what was once expressly fine art photography and commercial image making, as well as portraiture and semi-staged voyeurism. Alec is a member of Magnum Photos, the esteemed, invite-only, international photographic collective; he founded an experimental press, Little Brown Mushroom, a platform for collaborative projects in collaboration with an eclectic roster of artists. His photographs are in several major public and private collections (including the Walker Art Center, SFMoMA, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston). In our conversation we discuss shyness and community, photography as a vehicle to bolster human connection, the power that comes from embracing forms of awkwardness, empathy born from bearing witness, and creative agency and authorial intent.

Rimma Boshernitsan: How did you grow up?

Alec Soth: I grew up in Minnesota with my parents and my older brother. My mom was an interior designer, and my father was a lawyer.

I was a very introverted child. Some of this was probably informed by where I grew up. There’s something geographically that I’ve always thought was important to my development about this place -- growing up just past the suburbs. Growing up in a neighborhood that wasn’t quite a suburb and wasn’t quite a city required an effort to see friends. This certainly impacted how I grew to interact with the world. I spent a lot of time alone -- there were great big woods behind our house, fields, and a lot of space.

RB: Did you have a sense early on about who you wanted to “be” as an adult or how you wanted your life to evolve?

AS: No, not really. I didn’t have a plan. I remember being 14 or something like that and thinking ‘hmmm, geez, what am I going to do? Am I going to be a bank teller?’ I didn’t have a clear vision for what I could be. Some of us don’t -- our paths kind of find us by osmosis, or by way of someone else seeing something in us when we can’t.

It’s interesting to think about this now though, since I’m a parent with a 16 year old daughter who is struggling with her own kind of personal way-finding. It’s such a tricky thing, because when you’re young and searching for who or how to be in the world, it can seem as though everyone else is finding their path with ease.

RB: What aspects of your childhood/adolescence influenced your involvement in the arts?

AS: I was fortunate during my adolescence to have had a few teachers (usually in the humanities or the arts) who saw glimmers of potential beyond my extreme introversion and sought to engage me. In the 10th grade, I had an art teacher who spotted something and encouraged it in me. He was both a dynamic teacher and a practicing artist -- a painter -- and through him I got introduced to that world as a viable, dynamic thing. It was as if suddenly my eyes got wide to all sorts of possibilities and I realized I wanted to be an artist.

RB: Was that realization one of those rare, seemingly enviable, all-expansive, ‘suddenly - I’ve - figured - out - my - medium - and - my - motivations’ type of realizations where you find your focus and everything follows, or was it the beginning of a more gradual trajectory?

AS: The latter. I knew I wanted to be an artist, but I didn’t know exactly what that meant. It was through painting and later sculpture that I landed at Sarah Lawrence College with the intention of being an artist. I did well in advanced painting classes, but I felt like a fraud. I didn’t love painting. Somehow I knew I needed to be out in the world, which was a little odd because by nature I’m a homebody, but I felt the impulse and followed it. I started making sculptures outdoors and documenting them with a camera, which led me to photography by itself. After that, I discovered certain photographers and then I was off and running.

RB: You are a self-professed introvert who would often prefer to stay at home, and yet the nature of your work requires interaction with the outside world. How do you handle this contraction?

Monika. Warsaw . 2018 (I Know How Furiously You Heart Is Beating, MACK 2019) Monika. Warsaw. 2018 (I Know How Furiously You Heart Is Beating, MACK 2019)

AS: I’m not sure that I ‘handle’ it so much as I accept it. Contradiction is fundamental to my work. I’m not particularly in love with travel, and I’m a homebody -- yet I’ve made a career photographing strangers while traveling. In some ways, it’s ridiculous, because I am doing a thing that a whole swath of people dream about doing with their own lives, but it was never my dream. Peculiar. But there’s a tension involved in those activities that somehow stimulates the work.

RB: Your publishing imprint, Little Brown Mushroom, has a very distinct name. What significance does it have, is there a story behind it?

AS: There is a story, and it’s rather a long and convoluted one, but I’ll try and make it followable.

A few years ago, I was working on a project about men who wanted to run away from society. Eventually, the work from that project would become Broken Manual, the book I published in 2010 but at the time I was calling it something else. It was very definitely a midlife crisis project, and I found myself indulging in fantasies of running away myself, even creating an imaginary pseudonym. The pseudonym I came up with was Lester B. Morrison, which is kind of a play on ‘less is more'. I didn’t run away, but I did have the pseudonym, which I eventually developed further, started publishing things under, and which kind of developed its own identity.

The pseudonym Lester B. Morrison has the initials LBM. I started looking for other LBM acronym uses and I learned of one particular to mushroom hunters. For fungus and mushroom enthusiasts, LBM refers to “little brown mushroom” -- a very common mushroom but one that can’t be readily identified. An LBM/”little brown mushroom” is both ubiquitous and unknown, and it seemed suddenly very appropriate to use for some zines and things I wanted to make, strange little paper-bound things popping up almost out of nowhere that could be both ostensibly common yet unidentifiable when examined.

I started making these little zines in conjunction with the midlife-crisis-running-away-project and kept making them after I completed that project, and then something curious happened: I realized that despite my efforts to be a solitary artist, I found myself enjoying working on collaborations. I realized that I could make Little Brown Mushroom a ‘place’ where I could collaborate and play with others in a way that was separate from my solo work; analogous to a musician with a solo career who enjoys jamming. With Little Brown Mushroom, I could do these experimental jams with different writers and designers, and I did.

RB: Do mushrooms in general, or particular kinds of mushrooms, hold any personal meaning for you? I’m sure you’re asked variants of this question.

AS: (Laughs) No, no, it’s not what most people assume, which is that the name Little Brown Mushroom is somehow related to hallucinogens. It’s not at all, I have no experience with them. However, there is a protracted way in which mushrooms do have a kind of significance for me, but it’s more of an indexical one. When I first really got into art in high school, it coincided with my getting really into John Cage. From my late teens to my early twenties I deified him, or at least had a sustained kind of hero worship, i.e., I learned everything I could learn about his work, his practices, his aesthetic values, etc. and along the way, I learned he was a highly regarded mushroom hunter. Incidentally, there are some great pictures of him mushroom hunting. Anyway, the piece that ties John Cage to Little Brown Mushroom is that a while ago we ended up publishing a book which involved his texts. We worked closely with the Cage Foundation in conceiving the book, along with the photographer William Gedney (whose photos of Cage we employed in its creation), and what we ended up with was a very “Cage-ian” object itself, in that the book comes apart, has a lot of ‘chance’ elements, and can be reassembled. It was one of the best books we’ve ever published.

Mary, Milwaukee, WI (Postcard from America, Magnum, 2014)

RB: In preparation for our conversation, I re-read quite a few interviews you’ve given, and noticed a common theme in all of them. At some point, you are asked to discuss your thoughts on doubt/your complicated feelings about power dynamics and how they play out with your work as a photographer, and sometimes, guilt. I’ve been impressed with your candor and vulnerability when it comes to openly discussing these things, and I wonder if you might be willing to discuss them again here. For example, do you experience apprehension while making a photograph because you are going to benefit financially from it? Is there a relationship for you between checking/being mindful of your power as the person holding the camera and your knowledge that in the end, you’re the owner of the image and control the reception of the final product?

AS:: All of these are things I think about in a more or less ongoing way, and being aware of their potential as ‘problematic’ is part of my practice as an artist. For as long as I’ve had a career as a photographer I’ve had to give lectures on my work, which also means I’ve had to answer a lot of questions about it immediately following my talk. Invariably, the first questions will involve how I interact with my subjects, how do I approach people to be in my photographs, etc. After those get asked, I start getting questions about ethics, both as they functionally pertain to creating the work (like how does one get people to sign releases, etc.) and about whether or not I factor my own ethics into how I make images. When I’m asked if I believe I’m doing ‘good’ as a photographer, my stock answer has always been a complicated one. I’ve never felt that I’m ‘doing good,” honestly I’ve always felt like I was doing something vaguely kind of wrong, but I could retain that I wasn’t doing a lot of damage either.

Over time, my work and choice of subjects has evolved, as has my perspective about what I’m doing. I now give a lot more space to consider that my photographing someone for use in a project of my own might be really meaningful for them outside of the work. I still have complicated feelings about selling and distributing what I make, but not so much about the act of photography itself.

On that note, I have and can share a couple of stories from my most recent body of work about how my relationship to making portraits has changed. I photographed a woman in Dusseldorf and also interviewed her, because early on in that project I was trying to do both. The resulting picture wasn’t one that I used (it just wasn’t particularly great), but we had a really beautiful experience making it. Some time later, she came up to me at an art opening and remarked about how meaningful that shoot and conversation was to her. I realized that since the resulting picture never made it into the world, it was an experience we could both hold onto, that held meaning outside of whether it was bought or sold, but simply connection without any commercialization.

Similarly, awhile back I was in England, working on a project where I had asked friends to recommend me people who I might photograph. A friend of mine told me about someone he knew whose picture I should take. He insisted she had an ineffable quality about her that was worth encountering, and he knew I would probably not get another chance to meet her as she was dying. So, I met her, and I had the most incredible time with her. Photographing her was a really beautiful, meaningful encounter, but in the end I didn’t publish the image. The portrait was somehow too sweet, it wouldn’t have communicated what I wanted to an audience, so I didn’t publish it. After she passed away, I found myself the unexpected recipient of an unexpected letter from her boyfriend (a man I had never met), who wrote to thank me for the picture and share that he was glad it wasn’t published, because he now gets to hold onto it for himself. That part really struck me, how one can hold onto an image in a particular way that is very different to when it’s sold and distributed. The whole matter of photographic ownership/final project is very complicated, and I think somehow it will always be a kind of internal ethical conflict for me.

RB: That completely makes sense. I feel as though I understand your struggle though, because there’s not just one but many fine lines between power, vulnerability, perception and perspective (and you, as the artist, are largely in control of balancing how you deal with these things) at play in making images of people. I imagine that the people you have photographed cannot help but feel at least a little flattered when something they’ve participated in becomes more than a document of an experience and something more widely known.

AS: I’ve had enough feedback from subjects to confirm that yes, what you’re saying is true. Still, as you’ve observed, there’s a lot of things going on when I’m making work. I do bring this guilty feeling with me and sometimes it’s really irrational. Other times it is rational. I suppose one way I could change the dynamic would be to offer access to each subject after doing a shoot and let them choose which picture is their favorite, thus ceding creative control to the other person and giving them more power -- but that wouldn’t work for the art. I’m trying to make the most compelling picture, not the most flattering one. There’s a tension involved with all of this that I still haven’t resolved, and will probably follow me as long as I do what I do.

RB: In your practice, when you photograph subjects it’s often in the service of a larger project. Those subjects don’t have access to your vision, they can’t see where their portraits are going to fit into your project, so even if you wanted to give them more control of an image you can’t actually give them that control because to do so would take away the work. You want to help your subjects keep their agency in a moment, yet you need their moments to make the work. How do you balance these things?

AS: I think intention really matters. Like, for me, upholding an intention not to do harm and keeping consideration for the other person is really worthwhile. Every artist, every photographer, has to draw those lines for themselves.

RB: It seems like your work has taken on a different kind of meaning to you, as you started to photograph people again after taking a break for a few years. Like your presence as a photographer, in making the image, how you yourself felt in relation to your subjects, is different. Do you notice this? Would you say your sense of presence has shifted from the past to the present?

AS: Yes, but also keep in mind that everything else has changed too. We all change things. And so talking about myself now feels very different than it would have six months ago. I felt healthier before all of this publicity and selling work that’s taken place recently. I feel a little more fraught, but I’m taking this to mean that I need to refresh, adjust my perspective, and get in touch with different things. It’s all very much a process.

RB: On the subject of process, one thing I notice you’re willing to articulate is both how simultaneously intuitive your process is and how you grapple with the results of what you make . Like, your process is so intuitive that when you’re working, you don’t necessarily value the bits and pieces that come together to make the work -- but those bits and pieces are the things that later become paramount to an observer. There’s so many people learning and growing as a result of your intuition. It’s transformative for all parties, from the subject themselves to you to the people who buy your work -- not necessarily for the same reasons, but as a whole it works. You’re doing a service.

AS: Maybe. It’s funny, I suppose, how awkward I can become when talking about my work and my practice, about suggested or implicit voyeurism in my photographs, etc. I try to publicly expose my own internal questioning of these issues. I hope that maybe my attempts at transparency are useful to some people. For example, on Instagram, I’ve been having a debate with myself about Diane Arbus and a contemporary of hers and about how their different works lived in the world. They both had such a different relationship to how their works lived in the world than I do with my own, and so I’m questioning for myself, what is the best approach, or what paths do I want to go down, and what feels authentic.

RB: How do you view the role of human connection in your work? Is there a specific way that human connection affects how you think about your work?

AS: This might not be a direct answer but it’s what comes to mind: I read a quote from some writer recently who said that what makes him happy is the thought of a future stranger picking up his book and somehow feeling a little less lonely because of it. I can relate to this, the idea of protracted connection, or connection in separation. As we talked about earlier, when making the work, I will sometimes have genuine moments of connection with my subjects, but it doesn’t stop there. Afterwards, there are other avenues or possibilities for human connection, whether it's how or when certain pieces get exhibited, or something else. I suppose in a way, despite being markedly introverted and solitary by nature, human connection is fundamentally important to me both as an artist and a person in the world.

RB: What is your idea of the perfect happiness?

AS: I think we all know this kind of flow state where we’re each totally in the moment and totally absorbed. It’s not sustainable for anyone forever, but I think having as much of that state in one’s life as possible is great happiness. I think creating a life in which you can be in the moment as much as possible is a happy life.

Veronique’s View, Toulouse (I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, MACK 2019)